Just wanted to quickly notify you that I’m in the process of updating all the shader tutorials to XNA 4.0. A lot of people have asked me about it so I decided to do the job. ![]()

I’ll keep you posted once the updates are done!

Just wanted to quickly notify you that I’m in the process of updating all the shader tutorials to XNA 4.0. A lot of people have asked me about it so I decided to do the job. ![]()

I’ll keep you posted once the updates are done!

Now that you know how to use the RGB Camera data, it’s time to take a look at how you can use the depth data from the Kinect sensor.

It’s quite similar to getting data from the RGB image, but instead of RGB values, you have distance data. We will convert the distance into an image representing the depth map.

Initializing the Kinect Sensor

Not much new here since tutorial #2. In InitializeKinect() we enable the DepthStream and and listen to the DepthFrameReady event instead of ColorStream and ColorFrameReady as we did when getting the RGB image in tutorial #2.

private bool InitializeKinect()

{

kinectSensor.DepthStream.Enable(DepthImageFormat.Resolution640x480Fps30);

kinectSensor.DepthFrameReady += new EventHandler<DepthImageFrameReadyEventArgs>(kinectSensor_DepthFrameReady);

try

{

kinectSensor.Start();

}

catch

{

connectedStatus = "Unable to start the Kinect Sensor";

return false;

}

return true;

}

Here, we open the DepthStream and tell the sensor that we want to have depth data with the resolution of 640×480. We also create an event handler that kicks in everytime the Kinect got some data ready for us.

Converting the depth data

Now is the time for the meat of this tutorial. Here we get the depth data from the device in millimeter, and convert it into a distance we can use for displaying a black and white map of the depth. The Kinect device got a range from 0.85m to 4m (Xbox, the PC-version can see closer and further). We can use this knowledge to create a black and white image where each pixel is the distance from the camera. We might also get some unknown depth pixels if the rays are hitting a window, shadow, mirror and so on (these will have the distance of 0).

First of all, we grab the captured DepthImageFrame from the device. Then we copy this data and convert the depth frame into a 32bit format that we can use as the source for our pixels. The ConverDepthFrame function convert’s the 16-bit grayscale depth frame that the Kinect captured into a 32-bit image frame. This function was copied from the Kinect for Windows Sample that came with the SDK.

Let’s take a look at the code.

void kinectSensor_DepthFrameReady(object sender, DepthImageFrameReadyEventArgs e)

{

using (DepthImageFrame depthImageFrame = e.OpenDepthImageFrame())

{

if (depthImageFrame != null)

{

short[] pixelsFromFrame = new short[depthImageFrame.PixelDataLength];

depthImageFrame.CopyPixelDataTo(pixelsFromFrame);

byte[] convertedPixels = ConvertDepthFrame(pixelsFromFrame, ((KinectSensor)sender).DepthStream, 640 * 480 * 4);

Color[] color = new Color[depthImageFrame.Height * depthImageFrame.Width];

kinectRGBVideo = new Texture2D(graphics.GraphicsDevice, depthImageFrame.Width, depthImageFrame.Height);

// Set convertedPixels from the DepthImageFrame to a the datasource for our Texture2D

kinectRGBVideo.SetData<byte>(convertedPixels);

}

}

}

Notice that we didn’t manually create a Color-array as we did in the previous tutorial. You could have used this method instead of the Color-array method in tutorial #2 as well. Just wanted to show a few ways to do this just in case you need better control. 😉

And the ConvertDepthFrame function:

// Converts a 16-bit grayscale depth frame which includes player indexes into a 32-bit frame

// that displays different players in different colors

private byte[] ConvertDepthFrame(short[] depthFrame, DepthImageStream depthStream, int depthFrame32Length)

{

int tooNearDepth = depthStream.TooNearDepth;

int tooFarDepth = depthStream.TooFarDepth;

int unknownDepth = depthStream.UnknownDepth;

byte[] depthFrame32 = new byte[depthFrame32Length];

for (int i16 = 0, i32 = 0; i16 < depthFrame.Length && i32 < depthFrame32.Length; i16++, i32 += 4)

{

int player = depthFrame[i16] & DepthImageFrame.PlayerIndexBitmask;

int realDepth = depthFrame[i16] >> DepthImageFrame.PlayerIndexBitmaskWidth;

// transform 13-bit depth information into an 8-bit intensity appropriate

// for display (we disregard information in most significant bit)

byte intensity = (byte)(~(realDepth >> 4));

if (player == 0 && realDepth == 0)

{

// white

depthFrame32[i32 + RedIndex] = 255;

depthFrame32[i32 + GreenIndex] = 255;

depthFrame32[i32 + BlueIndex] = 255;

}

else if (player == 0 && realDepth == tooFarDepth)

{

// dark purple

depthFrame32[i32 + RedIndex] = 66;

depthFrame32[i32 + GreenIndex] = 0;

depthFrame32[i32 + BlueIndex] = 66;

}

else if (player == 0 && realDepth == unknownDepth)

{

// dark brown

depthFrame32[i32 + RedIndex] = 66;

depthFrame32[i32 + GreenIndex] = 66;

depthFrame32[i32 + BlueIndex] = 33;

}

else

{

// tint the intensity by dividing by per-player values

depthFrame32[i32 + RedIndex] = (byte)(intensity >> IntensityShiftByPlayerR[player]);

depthFrame32[i32 + GreenIndex] = (byte)(intensity >> IntensityShiftByPlayerG[player]);

depthFrame32[i32 + BlueIndex] = (byte)(intensity >> IntensityShiftByPlayerB[player]);

}

}

return depthFrame32;

}

What this function does is to convert the 16-bit format to a usable 32-bit format. It takes the near and far depth, and also the unknown depth (mirrors, shiny surfaces and so on) and calculates the correct color based on the distance.

This function requires a few variables. You can change the function so these are defined within if you want.

// color divisors for tinting depth pixels

private static readonly int[] IntensityShiftByPlayerR = { 1, 2, 0, 2, 0, 0, 2, 0 };

private static readonly int[] IntensityShiftByPlayerG = { 1, 2, 2, 0, 2, 0, 0, 1 };

private static readonly int[] IntensityShiftByPlayerB = { 1, 0, 2, 2, 0, 2, 0, 2 };

private const int RedIndex = 2;

private const int GreenIndex = 1;

private const int BlueIndex = 0;

Rendering

Last we render the texture using a sprite batch.

protected override void Draw(GameTime gameTime)

{

GraphicsDevice.Clear(Color.CornflowerBlue);

spriteBatch.Begin();

spriteBatch.Draw(kinectRGBVideo, new Rectangle(0, 0, 640, 480), Color.White);

spriteBatch.Draw(overlay, new Rectangle(0, 0, 640, 480), Color.White);

spriteBatch.DrawString(font, connectedStatus, new Vector2(20, 80), Color.White);

spriteBatch.End();

base.Draw(gameTime);

}

The result is something similar to this:

Download: Source (XNA 4.0 + Kinect for Windows SDK 1.0)

The entire source can be seen below:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Audio;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Content;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.GamerServices;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Graphics;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Input;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Media;

using Microsoft.Kinect;

namespace KinectFundamentals

{

/// <summary>

/// This is the main type for your game

/// </summary>

public class Game1 : Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Game

{

GraphicsDeviceManager graphics;

SpriteBatch spriteBatch;

Texture2D kinectRGBVideo;

Texture2D overlay;

// color divisors for tinting depth pixels

private static readonly int[] IntensityShiftByPlayerR = { 1, 2, 0, 2, 0, 0, 2, 0 };

private static readonly int[] IntensityShiftByPlayerG = { 1, 2, 2, 0, 2, 0, 0, 1 };

private static readonly int[] IntensityShiftByPlayerB = { 1, 0, 2, 2, 0, 2, 0, 2 };

private const int RedIndex = 2;

private const int GreenIndex = 1;

private const int BlueIndex = 0;

//private byte[] depthFrame32 = new byte[640 * 480 * 4];

KinectSensor kinectSensor;

SpriteFont font;

string connectedStatus = "Not connected";

public Game1()

{

graphics = new GraphicsDeviceManager(this);

Content.RootDirectory = "Content";

graphics.PreferredBackBufferWidth = 640;

graphics.PreferredBackBufferHeight = 480;

}

void KinectSensors_StatusChanged(object sender, StatusChangedEventArgs e)

{

if (this.kinectSensor == e.Sensor)

{

if (e.Status == KinectStatus.Disconnected ||

e.Status == KinectStatus.NotPowered)

{

this.kinectSensor = null;

this.DiscoverKinectSensor();

}

}

}

private bool InitializeKinect()

{

kinectSensor.DepthStream.Enable(DepthImageFormat.Resolution640x480Fps30);

kinectSensor.DepthFrameReady += new EventHandler<DepthImageFrameReadyEventArgs>(kinectSensor_DepthFrameReady);

try

{

kinectSensor.Start();

}

catch

{

connectedStatus = "Unable to start the Kinect Sensor";

return false;

}

return true;

}

void kinectSensor_DepthFrameReady(object sender, DepthImageFrameReadyEventArgs e)

{

using (DepthImageFrame depthImageFrame = e.OpenDepthImageFrame())

{

if (depthImageFrame != null)

{

short[] pixelsFromFrame = new short[depthImageFrame.PixelDataLength];

depthImageFrame.CopyPixelDataTo(pixelsFromFrame);

byte[] convertedPixels = ConvertDepthFrame(pixelsFromFrame, ((KinectSensor)sender).DepthStream, 640 * 480 * 4);

Color[] color = new Color[depthImageFrame.Height * depthImageFrame.Width];

kinectRGBVideo = new Texture2D(graphics.GraphicsDevice, depthImageFrame.Width, depthImageFrame.Height);

// Set convertedPixels from the DepthImageFrame to a the datasource for our Texture2D

kinectRGBVideo.SetData<byte>(convertedPixels);

}

}

}

// Converts a 16-bit grayscale depth frame which includes player indexes into a 32-bit frame

// that displays different players in different colors

private byte[] ConvertDepthFrame(short[] depthFrame, DepthImageStream depthStream, int depthFrame32Length)

{

int tooNearDepth = depthStream.TooNearDepth;

int tooFarDepth = depthStream.TooFarDepth;

int unknownDepth = depthStream.UnknownDepth;

byte[] depthFrame32 = new byte[depthFrame32Length];

for (int i16 = 0, i32 = 0; i16 < depthFrame.Length && i32 < depthFrame32.Length; i16++, i32 += 4)

{

int player = depthFrame[i16] & DepthImageFrame.PlayerIndexBitmask;

int realDepth = depthFrame[i16] >> DepthImageFrame.PlayerIndexBitmaskWidth;

// transform 13-bit depth information into an 8-bit intensity appropriate

// for display (we disregard information in most significant bit)

byte intensity = (byte)(~(realDepth >> 4));

if (player == 0 && realDepth == 0)

{

// white

depthFrame32[i32 + RedIndex] = 255;

depthFrame32[i32 + GreenIndex] = 255;

depthFrame32[i32 + BlueIndex] = 255;

}

else if (player == 0 && realDepth == tooFarDepth)

{

// dark purple

depthFrame32[i32 + RedIndex] = 66;

depthFrame32[i32 + GreenIndex] = 0;

depthFrame32[i32 + BlueIndex] = 66;

}

else if (player == 0 && realDepth == unknownDepth)

{

// dark brown

depthFrame32[i32 + RedIndex] = 66;

depthFrame32[i32 + GreenIndex] = 66;

depthFrame32[i32 + BlueIndex] = 33;

}

else

{

// tint the intensity by dividing by per-player values

depthFrame32[i32 + RedIndex] = (byte)(intensity >> IntensityShiftByPlayerR[player]);

depthFrame32[i32 + GreenIndex] = (byte)(intensity >> IntensityShiftByPlayerG[player]);

depthFrame32[i32 + BlueIndex] = (byte)(intensity >> IntensityShiftByPlayerB[player]);

}

}

return depthFrame32;

}

private void DiscoverKinectSensor()

{

foreach (KinectSensor sensor in KinectSensor.KinectSensors)

{

if (sensor.Status == KinectStatus.Connected)

{

// Found one, set our sensor to this

kinectSensor = sensor;

break;

}

}

if (this.kinectSensor == null)

{

connectedStatus = "Found none Kinect Sensors connected to USB";

return;

}

// You can use the kinectSensor.Status to check for status

// and give the user some kind of feedback

switch (kinectSensor.Status)

{

case KinectStatus.Connected:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Connected";

break;

}

case KinectStatus.Disconnected:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Disconnected";

break;

}

case KinectStatus.NotPowered:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Connect the power";

break;

}

default:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Error";

break;

}

}

// Init the found and connected device

if (kinectSensor.Status == KinectStatus.Connected)

{

InitializeKinect();

}

}

protected override void Initialize()

{

KinectSensor.KinectSensors.StatusChanged += new EventHandler<StatusChangedEventArgs>(KinectSensors_StatusChanged);

DiscoverKinectSensor();

base.Initialize();

}

protected override void LoadContent()

{

spriteBatch = new SpriteBatch(GraphicsDevice);

kinectRGBVideo = new Texture2D(GraphicsDevice, 1337, 1337);

overlay = Content.Load<Texture2D>("overlay");

font = Content.Load<SpriteFont>("SpriteFont1");

}

protected override void UnloadContent()

{

kinectSensor.Stop();

kinectSensor.Dispose();

}

protected override void Update(GameTime gameTime)

{

if (GamePad.GetState(PlayerIndex.One).Buttons.Back == ButtonState.Pressed)

this.Exit();

base.Update(gameTime);

}

protected override void Draw(GameTime gameTime)

{

GraphicsDevice.Clear(Color.CornflowerBlue);

spriteBatch.Begin();

spriteBatch.Draw(kinectRGBVideo, new Rectangle(0, 0, 640, 480), Color.White);

spriteBatch.Draw(overlay, new Rectangle(0, 0, 640, 480), Color.White);

spriteBatch.DrawString(font, connectedStatus, new Vector2(20, 80), Color.White);

spriteBatch.End();

base.Draw(gameTime);

}

}

}

Our first Kinect program will be using XNA 4.0 to create a texture that is updated with a new image from the Kinect Sensor every time a new image is created, thus displaying a video.

Note: This tutorial has been updated from Kinect for Windows SDK beta to Kinect for Windows SDK 1.0. The source-code is almost completely rewritten.

Setting up the project

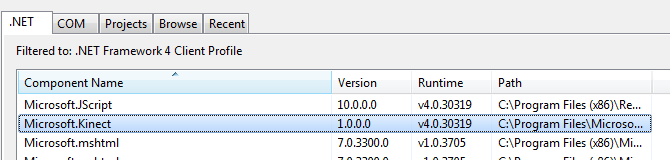

Create a new XNA Windows game and give it a name. To use the Kinect SDK, you will need to add a reference to it. This can be done by right clicking on the References folder, click Add Reference.. and in the .NET tab find Microsoft.Kinect.

Click OK to add it, and you will see it in the projects references.![]()

Next, you will need to add a using statement to it, by adding this line below the rest of the using statements:

using Microsoft.Kinect;

Creating and Initializing the KinectSensor object

Now we are ready to create the object that will “hold” the Kinect Sensor. The Kinect SDK have a class named KinectSensor that contains the NUI library. To get what you need our from the Kinect Sensor, instantiate an object from this class:

KinectSensor kinectSensor;

We also create a Texture2D object that will contain our images:

Texture2D kinectRGBVideo;

In the XNA’s Initialize function, we will need to listen to the StatusChanged event on KinectSensor.KinectSensors. This is a part of the KinectSensor library – making it possible to go through all connected Kinect-devices and check their status. By listening to this event handler, you can run code once the status changes on any of the connected devices.

protected override void Initialize()

{

KinectSensor.KinectSensors.StatusChanged += new EventHandler<StatusChangedEventArgs>(KinectSensors_StatusChanged);

DiscoverKinectSensor();

base.Initialize();

}

We also create a function called DiscoverKinectSensor(). This function will go through all connected Kinect-devices and when found a device, use it to set our kinectSensor instance, update a message the user can read and in the end Initialize it if connected.

private void DiscoverKinectSensor()

{

foreach (KinectSensor sensor in KinectSensor.KinectSensors)

{

if (sensor.Status == KinectStatus.Connected)

{

// Found one, set our sensor to this

kinectSensor = sensor;

break;

}

}

if (this.kinectSensor == null)

{

connectedStatus = "Found none Kinect Sensors connected to USB";

return;

}

// You can use the kinectSensor.Status to check for status

// and give the user some kind of feedback

switch (kinectSensor.Status)

{

case KinectStatus.Connected:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Connected";

break;

}

case KinectStatus.Disconnected:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Disconnected";

break;

}

case KinectStatus.NotPowered:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Connect the power";

break;

}

default:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Error";

break;

}

}

// Init the found and connected device

if (kinectSensor.Status == KinectStatus.Connected)

{

InitializeKinect();

}

}

Now we need to initialize the object to get the streams we want. We want out application to simply render what the Kinect can see (images from the RGB Camera). To do this, we tell the kinectSensor that we should enable the ColorStream, and what Format we want out. We also listen for the ColorFrameReady event whom will notify us if the Kinect got a new image ready for us. Once we have told the Kinect what it should produce for us, we can go ahead and start the device. Starting the device will make it create what we specified above – in this case, just the ColorStream.

private bool InitializeKinect()

{

kinectSensor.ColorStream.Enable(ColorImageFormat.RgbResolution640x480Fps30);

kinectSensor.ColorFrameReady += new EventHandler<ColorImageFrameReadyEventArgs>(kinectSensor_ColorFrameReady);

try

{

kinectSensor.Start();

}

catch

{

connectedStatus = "Unable to start the Kinect Sensor";

return false;

}

return true;

}

This makes the RGB Camera in the Kinect Sensor ready for use.

Getting images from the Kinect RGB camera

Now that the camera is ready and capturing images for us, we will need to copy the image from the Kinect-output to a Texture2D image.

This function is quite simple. It captures the image from the Kinect sensor, creates a Color array, fills it with the data from the captures image for each pixel, and then finally stores it in a Texture2d object. Let’s take a look at the EventHandler:

void kinectSensor_ColorFrameReady(object sender, ColorImageFrameReadyEventArgs e)

{

using (ColorImageFrame colorImageFrame = e.OpenColorImageFrame())

{

if (colorImageFrame != null)

{

byte[] pixelsFromFrame = new byte[colorImageFrame.PixelDataLength];

colorImageFrame.CopyPixelDataTo(pixelsFromFrame);

Color[] color = new Color[colorImageFrame.Height * colorImageFrame.Width];

kinectRGBVideo = new Texture2D(graphics.GraphicsDevice, colorImageFrame.Width, colorImageFrame.Height);

// Go through each pixel and set the bytes correctly.

// Remember, each pixel got a Rad, Green and Blue channel.

int index = 0;

for (int y = 0; y < colorImageFrame.Height; y++)

{

for (int x = 0; x < colorImageFrame.Width; x++, index += 4)

{

color[y * colorImageFrame.Width + x] = new Color(pixelsFromFrame[index + 2], pixelsFromFrame[index + 1], pixelsFromFrame[index + 0]);

}

}

// Set pixeldata from the ColorImageFrame to a Texture2D

kinectRGBVideo.SetData(color);

}

}

}

We start by opening the captured raw image. Then we copy all the data from it to a temporarily array of bytes. Then we create a color-array and the Texture2D-instance to have the same resolution as the captured Kinect-image is.

Then we go through each pixel and take the RGB value, one byte pr. channel. As the color-array is just a 1D-array, we must use the formula:

index = y * width + x

This will find the correct index for the given coordinate x,y.

Once we have all data, we can set the instance of the Texture2D data to the color-array.

Also, in the UnloadContent (or Dispose), add the following line:

protected override void UnloadContent()

{

kinectSensor.Stop();

kinectSensor.Dispose();

}

Rendering

We only need to render the Texture2D image as a normal texture:

protected override void Draw(GameTime gameTime)

{

GraphicsDevice.Clear(Color.CornflowerBlue);

spriteBatch.Begin();

spriteBatch.Draw(kinectRGBVideo, new Rectangle(0, 0, 640, 480), Color.White);

spriteBatch.Draw(overlay, new Rectangle(0, 0, 640, 480), Color.White);

spriteBatch.DrawString(font, connectedStatus, new Vector2(20, 80), Color.White);

spriteBatch.End();

base.Draw(gameTime);

}

This should render the image that the Kinect Sensor is taking, 30 images pr. second. Below is a screenshot from our application.

Download: Source (XNA 4.0, Kinect for Windows SDK 1.0)

The entire code can be seen below:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Audio;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Content;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.GamerServices;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Graphics;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Input;

using Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Media;

using Microsoft.Kinect;

namespace KinectFundamentals

{

/// <summary>

/// This is the main type for your game

/// </summary>

public class Game1 : Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Game

{

GraphicsDeviceManager graphics;

SpriteBatch spriteBatch;

Texture2D kinectRGBVideo;

Texture2D overlay;

KinectSensor kinectSensor;

SpriteFont font;

string connectedStatus = "Not connected";

public Game1()

{

graphics = new GraphicsDeviceManager(this);

Content.RootDirectory = "Content";

graphics.PreferredBackBufferWidth = 640;

graphics.PreferredBackBufferHeight = 480;

}

void KinectSensors_StatusChanged(object sender, StatusChangedEventArgs e)

{

if (this.kinectSensor == e.Sensor)

{

if (e.Status == KinectStatus.Disconnected ||

e.Status == KinectStatus.NotPowered)

{

this.kinectSensor = null;

this.DiscoverKinectSensor();

}

}

}

private bool InitializeKinect()

{

kinectSensor.ColorStream.Enable(ColorImageFormat.RgbResolution640x480Fps30);

kinectSensor.ColorFrameReady += new EventHandler<ColorImageFrameReadyEventArgs>(kinectSensor_ColorFrameReady);

try

{

kinectSensor.Start();

}

catch

{

connectedStatus = "Unable to start the Kinect Sensor";

return false;

}

return true;

}

void kinectSensor_ColorFrameReady(object sender, ColorImageFrameReadyEventArgs e)

{

using (ColorImageFrame colorImageFrame = e.OpenColorImageFrame())

{

if (colorImageFrame != null)

{

byte[] pixelsFromFrame = new byte[colorImageFrame.PixelDataLength];

colorImageFrame.CopyPixelDataTo(pixelsFromFrame);

Color[] color = new Color[colorImageFrame.Height * colorImageFrame.Width];

kinectRGBVideo = new Texture2D(graphics.GraphicsDevice, colorImageFrame.Width, colorImageFrame.Height);

// Go through each pixel and set the bytes correctly

// Remember, each pixel got a Rad, Green and Blue

int index = 0;

for (int y = 0; y < colorImageFrame.Height; y++)

{

for (int x = 0; x < colorImageFrame.Width; x++, index += 4)

{

color[y * colorImageFrame.Width + x] = new Color(pixelsFromFrame[index + 2], pixelsFromFrame[index + 1], pixelsFromFrame[index + 0]);

}

}

// Set pixeldata from the ColorImageFrame to a Texture2D

kinectRGBVideo.SetData(color);

}

}

}

private void DiscoverKinectSensor()

{

foreach (KinectSensor sensor in KinectSensor.KinectSensors)

{

if (sensor.Status == KinectStatus.Connected)

{

// Found one, set our sensor to this

kinectSensor = sensor;

break;

}

}

if (this.kinectSensor == null)

{

connectedStatus = "Found none Kinect Sensors connected to USB";

return;

}

// You can use the kinectSensor.Status to check for status

// and give the user some kind of feedback

switch (kinectSensor.Status)

{

case KinectStatus.Connected:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Connected";

break;

}

case KinectStatus.Disconnected:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Disconnected";

break;

}

case KinectStatus.NotPowered:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Connect the power";

break;

}

default:

{

connectedStatus = "Status: Error";

break;

}

}

// Init the found and connected device

if (kinectSensor.Status == KinectStatus.Connected)

{

InitializeKinect();

}

}

protected override void Initialize()

{

KinectSensor.KinectSensors.StatusChanged += new EventHandler<StatusChangedEventArgs>(KinectSensors_StatusChanged);

DiscoverKinectSensor();

base.Initialize();

}

protected override void LoadContent()

{

spriteBatch = new SpriteBatch(GraphicsDevice);

kinectRGBVideo = new Texture2D(GraphicsDevice, 1337, 1337);

overlay = Content.Load<Texture2D>("overlay");

font = Content.Load<SpriteFont>("SpriteFont1");

}

protected override void UnloadContent()

{

kinectSensor.Stop();

kinectSensor.Dispose();

}

protected override void Update(GameTime gameTime)

{

if (GamePad.GetState(PlayerIndex.One).Buttons.Back == ButtonState.Pressed)

this.Exit();

base.Update(gameTime);

}

protected override void Draw(GameTime gameTime)

{

GraphicsDevice.Clear(Color.CornflowerBlue);

spriteBatch.Begin();

spriteBatch.Draw(kinectRGBVideo, new Rectangle(0, 0, 640, 480), Color.White);

spriteBatch.Draw(overlay, new Rectangle(0, 0, 640, 480), Color.White);

spriteBatch.DrawString(font, connectedStatus, new Vector2(20, 80), Color.White);

spriteBatch.End();

base.Draw(gameTime);

}

}

}

Welcome to the first part of my Kinect Findamentals series. In this series, we will look at how you can implement your own Kinect-applications using XNA 4.0.

Update: This tutorial has been updated to using the February 2012 version of the SDK. Enjoy ![]()

What is the Kinect?

The Kinect is a motion sensing device for XBOX 360, and now also for Windows. It is a natural user interface for interacting with the XBOX 360 and Windows PC by using gestures and body movement, instead of a controller.

The Kinect Sensor

The Kinect Sensor device consists of an RGB camera taking 30 images pr. second (not a video stream) @ 640×480, and 15 images pr. second @ 1280×1024, depth cameras (infrared) and a multi-array mic.

Connecting the Kinect

Step 0

If you don’t have a Kinect for Windows Sensor, you can (probably) find it at your nearest electronics dealer or buy it online.

Step 1

Download and install the Kinect for Windows SDK:

http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/kinectforwindows/develop/overview.aspx

Step 2

Connect the Kinect device using the adapter for USB (if the plug is orange, don’t plug it, you will need the adapter) and Automatic Update will install the drivers.

Now, restart the computer.

If correctly installed, you can see the device in Device Manager (Control panel->System). ![]()

Once the Kinect is connected, you can find the microphone as any other microphone connected to your PC.

Testing the Kinect

There should be an application that you can use to view the skeletal. The application was installed with the Kinect SDK.

Now start the Kinect Sample Browser, select C# and run some of the examples to make sure it’s correctly installed.![]()

If the application give you some kind of error, please check this article by the kinect-team on what might be wrong.

http://support.xbox.com/en-US/kinect-for-windows/kinect-for-windows-info

The Kinect for Windows SDK is available, so feel free to try it out and see what you can make. I tried the API and like it a lot, easy to understand and follow.

See the launch event and video tutorials from here:

http://channel9.msdn.com/live

Download the Kinect SDK for Windows here:

http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/um/redmond/projects/kinectsdk/

Enjoy! ![]()

Just finished a 4k procedural graphic. The image is generated by an executable file with the size of 2.74 kb.

The image is generated by raymarching simple distance fields, and perlin noise.

Platform: Windows

API: OpenGL / GLSL

Code: digitalerr0r of Dark Codex

Download EXE (Various resolutions)

Download PNG (1680×1050)

The download contains the image, as well as EXE files for various screen resolutions.

A few years ago I read the article “Generating Complex Procedural Terrains Using the GPU” in GPU Gems 3. It covers a way to implement random landscapes using Noise, a great read if you are interested.

I’m just in the start phase, able to render some interesting landscape, but no texturing and so on.

The general algorithm is really simple. Just create a few layers of Perlin Noise on a plane.

I start by rendering a simple plane at the position –3 in the Y-axis:

Then, I add a few octaves of Noise to create an interesting landscape pattern:

As you can see, after only 8 octaves, the landscape is getting very interesting. You can play with the parameters for each layer, like amplitude, to create a mystical, evil looking landscape.

Next, I added another plane that’s just “straight” at Y = –3.2 to add a waterlevel:

A flight through the landscape can be seen below, enjoy. ![]()

A Mandelbulb fractal

The function I implemented is a bit wrong but the output was OK, running on about 30 FPS in 800×600 🙂

Only diffuse and specular light is used when rendering.

Rendered using DirectX, Shader Model 4.0.

Programming: digitalerr0r of Dark Codex (me ![]() )

)

Music: sabotender of Dark Codex

Two great sources on the Mandelbulb:

http://www.skytopia.com/project/fractal/mandelbulb.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mandelbulb

For the past six months, I have been spending quite some time on producing images using only the GPU.

Just wanted to share some of the images I have created. ![]()

Click the images to enlarge.

If you want to learn this, there is a very good paper (pdf) explaining it:

http://graphics.cs.uiuc.edu/~jch/papers/zeno.pdf

Enjoy! ![]()

If you are writing GLSL-shaders directly in a char-array instead of loading them from a file, and want to use #define or #extension and so on, you might get these errors:

0(1) : error C0114: expected ‘#extension <name> : <action>’

(0) : error C0000: syntax error, unexpected $end at token “<EOF>”

Say your fragment shader look like this:

static const char fragment_shader[] = \

“#extension GL_EXT_gpu_shader4 : enable”

“uniform vec4 test;”

“void main(void)”

“{“

“gl_FragColor = vec4(0, 0, 1, 1)*test;”

“}”;

When this get’s compiled, the “#extension GL_EXT_gpu_shader4 : enable” line is not properly read because there are no new line or a semicolon that can say that the line is read. When you creat this array, the shader really looks like this:

“#extension GL_EXT_gpu_shader4 : enableuniform vec4 test;void main(void){gl_FragColor = vec4(0, 0, 1, 1)*test;}”

A one-line shader.

Solution

To overcome this problem, you can manually add new-lines to the lines that needs this by using the char ‘\n’:

static const char fragment_shader[] = \

“#extension GL_EXT_gpu_shader4 : enable\n”

“uniform vec4 test;”

“void main(void)”

“{“

“gl_FragColor = vec4(0, 0, 1, 1)*test;”

“}”;

If the “#extension ..” line got shader code above as well, add a \n to the line above, or before #:

static const char fragment_shader[] = \

“uniform vec4 test;”

“\n#extension GL_EXT_gpu_shader4 : enable\n”

“void main(void)”

“{“

“gl_FragColor = vec4(0, 0, 1, 1)*test;”

“}”;

I know this might help somebody. Other solutions to similar problems are to use the Advanced Save function in Visual Studio to change the encoding of the file, or to pass in the array-length when writing compiling the shader.